When it comes to poker, sports betting or any other game of chance your profits are almost never determined by your skills alone, but also by your opponents’ skills.

I was merely in the upper middle class of poker players and needed to be in a game with some bad ones to be a favourite to make money. Fortunately, there were plenty of these bad players – what poker players call fish – during the poker boom years.

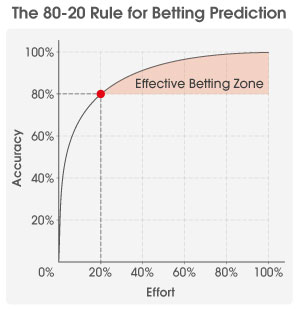

There is a learning curve that applies to poker and to most other tasks that involve some type of prediction. The key thing about a learning curve is that it really is a curve: the progress we make at performing the task is not linear. Instead, it usually looks something like the figure below – what I call the Pareto Principle of Prediction.

What you see is a graph that consists of effort on one axis and accuracy on the other. You could label the axes differently – for instance, experience on the one hand and skill on the other. But the same general idea holds. By effort or experience I mean the amount of money, time, or critical thinking that you are willing to devote toward a predictive problem. By accuracy or skill I mean how reliable the prediction will prove to be in the real world.

The name for the curve comes from the well-known business maxim called the Pareto principle or 80-20 rule (as in: 80 percent of your profits come from 20 percent of your customers). As I apply it here, it posits that getting a few basic things right can go a long way. In poker, for instance, simply learning to fold your worst hands, bet your best ones, and make some effort to consider what your opponent holds will substantially mitigate your losses. If you are willing to do this, then perhaps 80 percent of the time you will be making the same decision as one of the best poker players in the world – even if you have spent only 20 percent as much time studying the game.

This relationship also holds in many other disciplines in which prediction is vital. The first 20 percent often begins with having the right data, the right technology, and the right incentives. You need to have some information – more of it rather then less, ideally – and you need to make sure it is quality-controlled. You need to have some familiarity with the tools of your trade – having top-shelf technology is nice, but it’s more important that you know how to use what you have. You need to care about accuracy – about getting at the objective truth – rather than about making the most pleasing or convenient prediction.

Then you might progress to a few intermediate steps, developing some rules of thumb (heuristics) that are grounded in experience and common sense and some systematic process to make a forecast rather than doing so on an ad hoc basis.

These things aren’t exactly easy – many people get them wrong, but they aren’t hard either, and by doing them you may be able to make predictions 80 percent as reliable as those of the world’s foremost expert.

Sometimes, however, it is not so much how good your predictions are in an absolute sense that matters but how good they are relative to the competition. In poker, you can make 95 percent of your decisions correctly and still lose your shirt at a table full of players who are making the right move 99 percent of the time. Likewise, beating the stock market requires outpredicting teams of investors in fancy suits with MBAs from Ivy League schools who are paid seven-figure salaries and who have state-of-the-art computer systems at their disposal. Likewise, beating the most effective bookmakers in the sports betting market (e.g. Pinnacle, SBO, IBC) requires a very very good prediction model simply because they don’t make too many errors themselves. Compare that to the soft bookmakers like William Hill, Coral, Marathonbet and you will find that you just need to get a few basic things right to beat them.

In cases like these, it can require a lot of extra effort to beat the competition. You will find that you soon encounter diminishing returns. The extra experience that you gain, the further wrinkles that you add to your strategy, and the additional variables that you put into your forecasting model – these will only make a marginal difference. Meanwhile, the helpful rules of thumb that you developed – now you will need to learn the exceptions to them.

However, when a field is highly competitive, it is only through this painstaking effort around the margin that you can make any money. There is a “water level” established by the competition and your profit will be like the tip of an iceberg: a small sliver of competitive advantage floating just above the surface, but concealing a vast bulwark of effort that went in to support it.

I’ve tried to avoid these sort of areas back in the poker days and also try to avoid these areas in my betting today. Instead, I’ve been fortunate enough to take advantage of fields where the water level was set pretty low, and getting the basics right counted for a lot. I’m choosing my enemies very well!

If you have strong analytical skills that might be applicable in a number of disciplines, it is very much worth considering the strength of the competition. It is often possible to make a profit by being pretty good at prediction in fields where the competition succumbs to poor incentives, bad habits, or blind adherence to tradition – or because you have better data or technology than they do. It is much harder to be very good in fields where everyone else is getting the basics right – and you may be fooling yourself if you think you have much of an edge.

In general, society does need to make the extra effort at prediction, even though it may entail a lot of hard work with little immediate reward – or we need to be more aware that the approximations we make come with trade-offs. But if you’re approaching prediction as more of a business proposition, you’re usually better off finding someplace where you can be the big fish in a small pond.

[twitter-follow screen_name=’BettingIsCool’]